In their work, the researchers found a number of factors - some cultural, some not - that can impact the reliability of results gleaned from Big Five personality assessments administered in developing countries. And this is problematic, the researchers say, because most personality tests used in developing countries are modeled on the ones used in white, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic societies (or, more concisely, WEIRD, an acronym used in the research community).

But a new analysis by an international research team highlights an important caveat when it comes to administering cookie-cutter personality tests across cultures: these tests aren’t one-size-fits-all. Whether these personality traits are truly universal is still a matter of debate.

Insights gleaned from personality tests based on the Big Five framework are frequently used to understand trends related to issues like crime, education, employment, wages and more.

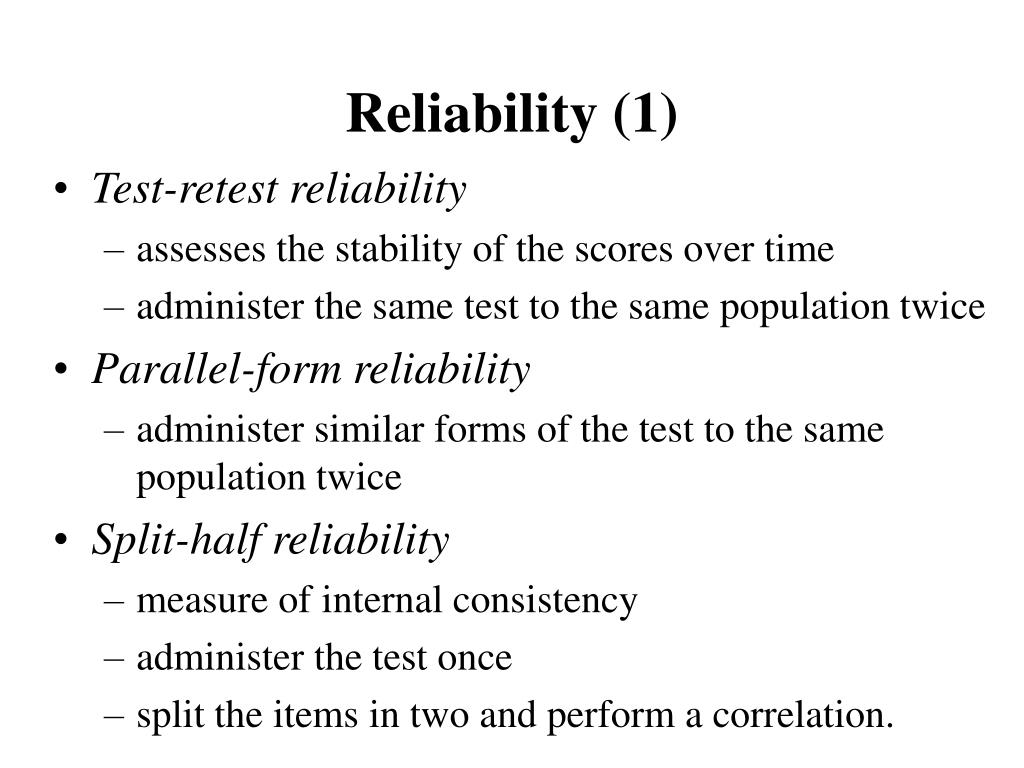

The thinking is that we’re all pretty much made up of the same five core ingredients, even if the measurements differ from person to person. It’s called the “Big Five” personality model, and it assumes that each of our personalities are a unique blend of a handful of traits: extraversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness and neuroticism. A lot of contemporary psychology research is based on the assumption that there are five basic dimensions of personality that define people around the world.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)